We published our studies in these peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Overview

We conducted our first study of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines (VSTAG, now known as CSTAG) in 2002 and since then have accumulated a large body of scientific research supporting our model. This research was conducted through the University of Virginia and published in leading peer-reviewed journals. In 2013, VSTAG was recognized as an evidence-based practice by the National Registry of Evidence-based Programs and Practices (NREPP) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. To qualify as an evidence-based practice, NREPP required 3 controlled studies showing the effects of the program. The Bureau of Justice Assistance defines an evidence-based practice as one supported by controlled studies. VSTAG is the only threat assessment model that has been tested in controlled studies and fully meets federal criteria for an evidence-based practice.

Some of our supporting research is summarized below. We would be pleased to send you copies of any of our studies. A PDF containing 20 studies can be downloaded here. More information on threat assessment research can be found at the University of Virginia website for the Youth Violence Project. Here is an overview article describing our model. Note that the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines was renamed the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines in 2018.

Summary

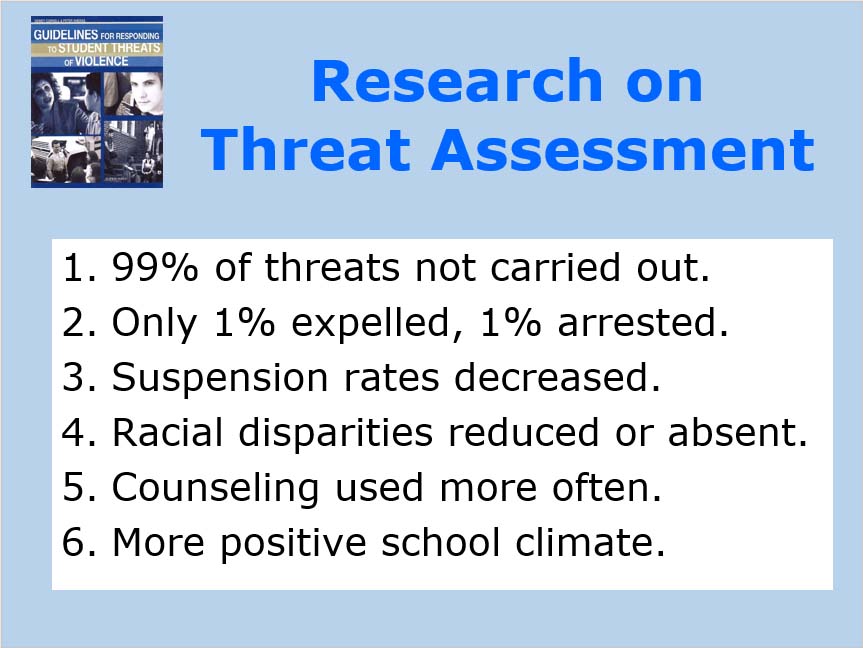

In summary, across hundreds of cases in multiple studies we have found that 99% of threats made by students who receive a threat assessment are not carried out. The small number of threats that were carried out involved fights that resulted in no serious injury. We have also found that only about 1% of these students are expelled from school and only about 1% are arrested. Most threats are resolved without school suspension and the overwhelming majority of students are able to continue in their original school.

Across multiple studies, schools have seen a decrease in their use of suspension out of school, both for the students who receive a threat assessment AND for the general student population. We have also seen reductions in the racial disparities in school suspension, especially the higher rate of suspension for Black students compared to White students.

Our randomized controlled trial showed a large increase in the use of counseling for students who received a threat assessment.

Finally, surveys of school climate found that both students and teachers in schools using threat assessment report a more positive school climate than students and teachers in schools not using the VSTAG model. Students report less bullying and more willingness to seek help from adults at school. Teachers report feeling safer.

First study - Initial Field test

Our first study was a field test conducted in 35 schools that recorded 188 student threat assessments over one school year. Threat cases were identified at all grade levels and involved threats to kill, shoot, stab, fight, or commit some other violent act toward others. This study pioneered the use of our decision tree to evaluate the seriousness of a threat and take appropriate action to reduce the threat of violence. The majority of cases (70%) were resolved quickly as transient threats and more serious cases (30%) required a more extensive response as substantive threats. Follow-up interviews with school staff found that none of the threatened acts of violence were carried out. Half of the students received a short-term suspension and 3 students (with numerous other disciplinary infractions) were expelled. Only 12 students were placed in an alternative school. This study was published in School Psychology Review, the flagship journal of the National Association of School Psychologists (NASP).

Cornell, D., Sheras, P. Kaplan, S., McConville, D., Douglass, J., Elkon, A., Knight, L., Branson, C., & Cole, J. (2004). Guidelines for student threat assessment: Field-test findings. School Psychology Review, 33, 527-546.

SEcond Study - Urban Field test

Our second field test was conducted in Memphis City Schools, which served a large, racially diverse urban population with many low income students residing in high crime neighborhoods. A central threat assessment team evaluated 209 cases in which a student was recommended for long-term suspension or expulsion because of a threat to commit a violent act. More than one-third of these students were receiving special education services, and three-fourths had been retained at least one grade. However, the threat assessment team was able to resolve the threats with no reported acts of violence. Approximately half of the cases were resolved as transient threats and half were considered substantive. In each case, the team developed a plan to resolve the threat, take appropriate protective action when needed, and provide needed educational and mental health services. Almost all of the students were able to continue their education and discipline referrals for returning students dropped 50% from their previous levels. This study was published in the Behavioral Disorders, the journal of the Council for Children with Behavioral Disorders.

Strong, K., & Cornell, D. (2008). Student threat assessment in Memphis City Schools: A descriptive report. Behavioral Disorders, 34, 42-54.

THIRD STUDY - CONTROLLED STUDY

Our third study was retrospective, correlational study using a quasi-experimental design that compared 95 high schools using VSTAG with 131 high schools using an alternative threat assessment model or 54 high schools not using threat assessment. On a statewide school climate survey, students in schools using VSTAG reported less bullying and greater willingness to seek help from adults at school. School records showed fewer long-term suspensions in VSTAG schools. These results controlled for school size, minority composition, family income level, neighborhood violent crime,and extent of security measures in schools. This study was published in School Psychology Quarterly, the School Psychology Division journal of the American Psychological Association.

Cornell, D., Sheras, P., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2009). A retrospective study of school safety conditions in high schools using the Virginia Threat Assessment Guidelines versus alternative approaches. School Psychology Quarterly, 24, 119-129.

FOURTH STUDY - PRE-POST CONTROLLED STUDY

Our fourth study was a pre-post examination of changes in suspension rate before and after implementation of VSTAG in 23 high schools and compared to 26 non-VSTAG high schools in a control group. After training, school administrators and other staff demonstrated increased knowledge of threat assessment principles and decreased commitment to zero tolerance discipline. VSTAG schools showed a 52% reduction in long-term suspensions and a 79% reduction in bullying infractions from the pre-training year to the post-training year. This study was published in NASSP Bulletin, the journal of the National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Cornell, D., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2011). Reductions in long-term suspensions following adoption of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines. Bulletin of the Nat Assoc of Secondary School Principals, 95, 175-194.

FIFTH STUDY - RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL

Our fifth study was a randomized controlled trial that compared 20 schools (elementary, middle, and high) trained in VSTAG with 20 control schools waiting one year before training. Based on 200 cases, students in schools that had threat assessment training were 4 times more likely to receive counseling and 2.5 times likely to have parental involvement in their cases. They were much less likely to be suspended or removed from the school and placed in an alternative school. In the control group, students who made threats typically were given a long-term suspension and/or transferred to another school. They did not receive counseling and their parents were notified by a letter or phone call that their child was being disciplined for a threat. This study provided strong evidence that threat assessment training propelled school teams to make substantial changes in how they handled student threats.

Cornell, D., Allen, K., & Fan, X. (2012). A randomized controlled study of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines in grades K-12. School Psychology Review, 41, 100-115.

SIXTH STUDY - MIDDLE SCHOOL CONTROLLED STUDY

Our sixth study used a retrospective, quasi-experimental design to compare 166 middle schools using VSTAG to 199 middle schools not using threat assessment and 47 middle schools using a locally developed threat assessment model. Based on school records, VSTAG schools had lower suspension rates than both of the control group schools. According to a statewide school climate survey, students in VSTAG schools reported fairer discipline and lower levels of peer aggression than students in the control group schools. Teachers reported feeling safer in the VSTAG schools than in the control group schools. All analyses controlled for school size, minority composition, and family income. This study was published in the Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, a journal of the American Psychological Association.

Nekvasil, E., Cornell, D. (2015). Student threat assessment associated with positive school climate in middle schools. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management 2, 98-113. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tam0000038

Seventh STUDY - comparison of two models

Our seventh study compared disciplinary consequences for 657 students in 260 schools using the Comprehensive Student Threat Assessment Guidelines (CSTAG) with a comparison group of 661 students in 267 schools using a more general threat assessment approach taught by the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services. Students who received a threat assessment in CSTAG schools were much less likely to be suspended or expelled from school, and half as likely to be subject to law enforcement actions (such as arrest or court charges) than students who received a threat assessment in the comparison group schools. These analyses controlled for school characteristics (enrollment size, percentage of low income and minority students) and student characteristics (grade level, gender, race, and special education status). This study was published in the Journal of School Violence.

Maeng, J., Cornell, D., & Huang, F. (2020). Student threat assessment as an alternative to exclusionary discipline. Journal of School Violence, 19, 377-388. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2019.1707682

reference list

Here is a list of 20 studies, including those summarized above, which are reports of original research on our threat assessment model (originally the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines, now the Comprehensive School Threat Assessment Guidelines). There are many other articles and book chapters that describe the Guidelines or summarize research about it, but the ones listed below constitute the primary research base. Copies of any of our work are available upon request. Download a document containing these 20 studies here. Additional information can be found on the University of Virginia website for the Youth Violence Project directed by Dr. Cornell.

Field Tests

Cornell, D., Sheras, P. Kaplan, S., McConville, D., Douglass, J., Elkon, A., Knight, L., Branson, C., & Cole, J. (2004). Guidelines for student threat assessment: Field-test findings. School Psychology Review, 33, 527-546.

Kaplan, S., & Cornell, D. (2005). Threats of violence by students in special education. Behavioral Disorders, 31, 107-119.

Strong, K., & Cornell, D. (2008). Student threat assessment in Memphis City Schools: A descriptive report. Behavioral Disorders, 34, 42-54.

Controlled Studies

Cornell, D., Sheras, P., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2009). A retrospective study of school safety conditions in high schools using the Virginia Threat Assessment Guidelines versus alternative approaches. School Psychology Quarterly, 24, 119-129.

Cornell, D., Gregory, A., & Fan, X. (2011). Reductions in long-term suspensions following adoption of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines. Bulletin of the National Association of Secondary School Principals, 95, 175-194.

Cornell, D., Allen, K., & Fan, X. (2012). A randomized controlled study of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines in grades K-12. School Psych Review, 41, 100-115.

Nekvasil, E., Cornell, D. (2015). Student threat assessment associated with positive school climate in middle schools. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management 2, 98-113. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tam0000038

Maeng, J., Cornell, D., & Huang, F. (2019). Student threat assessment as an alternative to exclusionary discipline. Journal of School Violence, doi: 10.1080/15388220.2019.1707682

Disciplinary Outcomes and Race/Ethnicity

JustChildren and Cornell, D. (2013). Prevention v. punishment: Threat assessment, school suspensions, and racial disparities. http://curry.virginia.edu/uploads/resourceLibrary/UVA_and_JustChildren_Report_-_Prevention_v._Punishment.pdf

Cornell, D., Maeng, J., Huang, F., Shukla, K., & Konold, T. (2018). Racial/ethnic parity in disciplinary consequences using student threat assessment. School Psychology Review, 47, 183-195. doi: 10.17105/SPR-2017-0030.V47-2

Cornell, D. & Lovegrove, P. (2015). Student threat assessment as a method for reducing student suspensions. In D. Losen (Ed.), Closing the School Discipline Gap: Research for Policymakers (pp. 180-191). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Studies of Training Effects

Allen, K., Cornell, D., Lorek, E., & Sheras, P. (2008). Response of school personnel to student threat assessment training. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 19, 319-332.

Stohlman, S., & Cornell, D. (2019). An online educational program to increase student understanding of threat assessment. Journal of School Health, 89 (11), 899-906. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12827

Stohlman, S., Konold, T., & Cornell, D. (2020). Evaluation of threat assessment training for school personnel. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/tam0000142

Studies of Implementation

Burnette, A. G., Datta, P. & Cornell, D. G. (2018). The distinction between transient and substantive student threats. Journal of Threat Assessment and Management, 5, 4-20. http://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-56103-001

Burnette, A.G., Huang, F., Maeng, J.L., & Cornell, D. (2018). School threat assessment versus suicide assessment: Statewide prevalence and case characteristics. Psychology in the Schools,1-15. doi: 10.1002/pits.22194

Cornell, D., & Maeng, J. (2018). Statewide implementation of threat assessment in Virginia K-12 schools. Contemporary School Psychology, 22, 116-124. doi: 10.1007/s40688-017-0146-x

Cornell, D., Maeng, J., Burnette, A.G., Jia, Y., Huang, F., Konold, T., Datta, P., Malone, M., Meyer, P. (2017). Student threat assessment as a standard school safety practice: Results from a statewide implementation study. School Psychology Quarterly. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/spq0000220

Burnette, A. G., Konold, T., & Cornell, D. (2019). Grade-level distinctions in student threats of violence. Journal of School Violence. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2019.1694031

Maeng, J., Malone, M., & Cornell, D. (2020). Student threats of violence against teachers: Prevalence and outcomes using a threat assessment approach. Teacher and Teacher Education, 87, 1-11. doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102934

University of Virginia research team, 2017-18